Main Page

Contents

A Blueprint and Implementation of a Public Data Ecosystem

Overview

The open data movement is gaining more momentum and is based on the assumption that more intensive and creative use of information and technology can improve policy-making and generate new forms of public value. Making data available for public use promotes transparency and accountability, economic development and expanded networks for knowledge creation. Past efforts in making data public has resulted in data being published in an ad-hoc manner, often through grass-roots efforts, with little consideration of access management, accountability or analytics. Consumers of public data want assurance that the data collection, management, access and dissemination practices used result in data provided that is valid, sufficient and appropriate for policy analysis or any other use. Data publishers must adhere to lifecycle processes in order to assure that the data accurate but is also fit for use considering both subjective perceptions and objective assessments which will have a bearing on the extent to which users are willing and able to use information. A systematic approach with an enterprise lifecycle perspective must be used to enable the full potential of open data. The most effective open data ecosystem produces benefits for the data consumer and the data provider but requires a structured, governed approach for supporting open data use. A civic effort in Minnesota has created a blueprint that addresses the strategy, design, deployment, operation and continual improvement of a public storefront to publish, discover, govern and manage publicly available data.

Summary: There are many social and economic benefits to making data available for public use, including transparency, accountability, economic development, and knowledge creation. The most effective system for publishing and delivering data requires a structured, governed approach designed from a lifecycle perspective for supporting data use.

Business Value and Return on Investment

The business value and return on investment of making public data available cannot be quantified in quantitative terms. A business makes decisions on the basis of quantifiable information that is used to develop a return on investment (ROI). If the ROI is within range of investment criteria, the decision to invest is easier to make. When it comes to making data open, the question for the government domain to answer is what is the cost of doing so and what is the expected business value since ROI cannot be determined in quantifiable terms. The value proposition of open data is associated with: 1) transparency and accountability, 2) economic development and smart disclosure, and 3) expanded policy networks for knowledge creation. A McKinsey report [1] expands on an important topic contained in a prior report[2] by McKinsey, which suggests that government can promote open data, and participates in over $3 trillion in economic value. Value creation can be enabled through promoting better decision making (more information results in better decisions), stimulating development of new products and services, and increasing transparency and improving accountability. Alex Howard[3] has discussed how open government promotes transparency and accountability, which is at the core of how government is thought about. When budgets are constrained, government officials question the value of each spending decision. Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, has said that increased transparency into a state’s finances and services directly relates to the willingness of businesses and other nations to invest in that government entity. The business value of open government is not always clear especially with respect to investment or outcomes. “Reactive” or “proactive” disclosure of information will affect the proliferation of data made available through public means. Reactive disclosure means that a question needs to be asked before an answer is given[4] while proactive disclosure is the release of information before it is requested. Open data policies and laws provide an opportunity not just to update and improve access to information that is already available but to specify that new data sets and records be published in a proactive manner hence influencing the use of data for public and business decisions. These open data efforts must be funded, however, and compete for budget dollars that may have greater public benefit than just simply the release of publicly available open data.

The challenges with releasing public data, in order to capitalize on perceived business value, require that effort be put into a comprehensive effort to manage, govern and make available public information and that a more systematic and structured approach should be considered in order to realize the potential business value of making public data available. The process of cleaning and preparing data to be published has returns for workers inside government itself and should be considered. A McKinsey[5] report indicates that government workers spend 19% of their time looking for information. The process of opening up public data clearly has benefits (and business value) for both external and internal users of this data.

What is the business value for a government domain to spend resources on opening up public data? There will be value for constituents (individual and commercial) who make use of the data to promote public or societal awareness and who develop commercial applications that are used for commercial purposes. The value to the government entity making the data available can have political, societal, and economic benefits. Users of the data can be important indicators of business activity and provide analytics to government entities to gain more insight into potential future economic value.

What data is made available and how to make it available are important parameters that need to be addressed in any public data initiative. In this sense, it is worthwhile to look at the delivery of open data to public consumers as a lifecycle process where data creation, data quality, data availability and data governance are key to assuring users that a rigorous enterprise approach to delivering data is in place making them more comfortable with the use and long term availability of the data.

Summary: There is great value generated by making public data available; in the U.S there is an estimated annual economic benefit of $1.1 trillion, due in part to increased efficiency and development of new products and services. Benefits can be difficult if not impossible to quantify directly as a return on investment and instead are better visualized as a value-add to constituents, governments, and companies; additionally, changing existing systems that are staff-time intensive (such as Data Practices Act requests) can reduce costs.

Government Domains

Governments collect or generate much data for their own purposes or from their own operations. If governments did not gain a net benefit from collecting and using data, they would not collect it to begin with. The U.S. Federal government has taken a lead in making open data available to the public. It recognizes information as a valuable national resource and a strategic asset to the Federal Government, its partners and the public. Its stated goals are to manage information as an asset throughout its life cycle to promote openness and interoperability and properly safeguard systems and information. Managing government information as an asset is expected to increase operational efficiencies, reduce costs, improve services, support mission needs, safeguard personal information and increase public access to valuable government information[6]. For example, the Federal Government website, data.gov, currently (September, 2014) has 108,498 data sets available on the data.gov portal.

The Federal Government has more resources available to it to invest in the development and delivery of an open data portal. Any government domain has the ability to gain value from making public data open and available but may not have the financial resources to invest in the infrastructure resources to make it available. To that extent, it is likely that smaller government domains may need to take advantage of larger domains that do have the ability to invest in open data initiatives.

All government domains, including federal, state, regional, county and city governments, should consider making their data available to the public. Because of the initial costs of making data available, not all entities will be able to make their data available. Funding may not be available at all because of the initial costs of a portal that will make the open data available to the public. To reduce the costs of providing open data to the public, small governments (e.g., small cities) could mutualize their expenses with other smaller entities or rely on other larger government infrastructure provided to share public data.

Summary: Governments can capture many benefits by making their data open, including: increased efficiency, reduced costs, improved services, support of their mission, and safeguarding of systems and information. It should be acknowledged that financial resources will be required to make data openly available, but a systematic view of costs for the existing system should be considered along with estimates of these benefits to the government and its constituents.

Stakeholders

There is general agreement among researchers that the public sector is complex and involves a variety of stakeholders [7]. Chircu[8] has shown that e-government projects are characterized by many stakeholders with multiple value dimensions (financial, social and political) but argues that few government studies adopt a multi-dimensional perspective incorporating all value dimensions and relevant stakeholders. Most studies in open data address the high level stakeholders, i.e., “the government”, “businesses” and “the public” as stakeholders. Identification of the stakeholders associated with a government open data initiative is important in order to determine costs and benefits. The benefits need to be addressed from a technical implementation perspective since there will be functions to be provided (through electronic means) in order to satisfy the information needs of the needs of the stakeholder and the cost of providing such information.

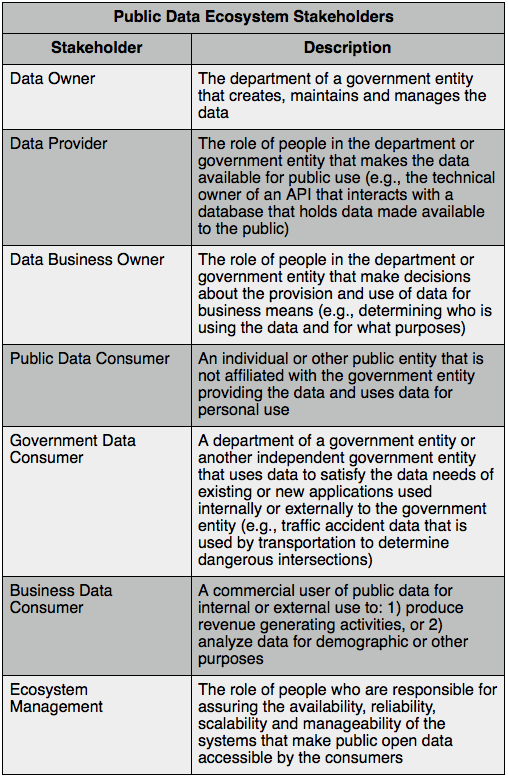

A stakeholder model for a public data ecosystem has been defined and is listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Public Data Ecosystem Stakeholders

The stakeholder model is used to determine information needs and technical infrastructure requirements for functions provided or managed by the respective stakeholder.

Summary: The stakeholder model is used to determine information needs and technical infrastructure requirements for functions provided or managed by the respective stakeholder.

Business Models

The exploration of potential business models around government open data initiatives aims to mitigate the risk of using public data when government funding is cut resulting in a reduced level of service to the consumers of public data. Reliance on the continual funding of the government entity providing the data is directly related to the perceived value that government is realizing from providing such public data. More importantly, an open data initiative may never get off the ground because of the lack of funding by the government entity. Even when funding is made available, it may not be at the levels required to get an open data initiative up and running. An analysis of potential public-private business models provides some reasonable alternatives that a government entity could adopt in order to deliver open data. Public and private sector organizations can learn from each other: 1) the private sector’s delivery model is motivated by profit gains, and 2) the public sector’s operating models are focused on well-documented quality measures and the risks associated with political priorities which are important elements in the drive for value. To put this into perspective, Hedman, et. al. [9] discusses a business model framework for public private partnership called the 3P Framework. Society requires public and private organizations to collaborate in solving many of the world’s problems. Collaboration between public and private organizations is not easy with one of the main inhibitors being the underlying business models and underlying strategies. Hedman, et. al. indicates that one of the key problems in collaborative efforts is revenue and cost allocation. Figure 1. below presents that 3P Business Model Framework developed by Hedman, et. al. File:Business Model.png Figure 1. The Public Private Partnership (3P) Business Model Framework (from Hedman, et. al.)

Briefly, the parts to this model (by example) are described as follows: 1. The user of e-services captures the competitive space or the market with users and alternative offerings or distribution channels. 2. Value proposition is often referred to as the offering where its theoretical roots are the generic strategies of differentiation and cost leadership. Offerings are usually a bundling of services or products. 3. The revenue model describes how an organization creates value for itself. 4. Business processes and organization structure or governance addresses the activities performed to acquire and transform resources into value propositions and deliver it to users. 5. Resources and network partners address vital resources of the partnership. There is a causal link between resources, business processes and value propositions. Value is ultimately determined by how well the resource improves cost or price (or customer perceived quality). 6. The cost model defines the drivers of cost. Generic drivers of cost and value include scale, capacity, utilization, linkage, interrelationships, vertical integration, local, timing, learning, policy decisions and government regulations. 7. Suppliers and external agencies address an organization’s acquisition of its inputs (resources) such as labor, raw material and financial capital. Policy makers and legal bodies are influential entities that both set the rules and control the market. 8. Evolution and management relate to the fact that business models evolve over time and must be managed and continually improved.

Public-private partnerships have the potential to: 1) assist in the initiation of public open data programs where the cost to start is prohibitive to the government organization, 2) sustain public data initiatives in the absence of appropriate government funding, and 3) provide better quality of service and lifecycle processes.

Various cost models have been discussed in research addressing the model options that a government might have in making open data available to the public. Pollock[10] discussed the economics of public sector information and public sector information holders (PSIH) and the two-sided nature of the PSIH. A PSIH is a government entity as defined in this study. Any information holder (refer to the Stakeholder discussion above) can be seen as having two sides to their operation: 1) the input (write/update) and the output (read/use) side. A government entity seeking to fund the production and maintenance of datasets has three possible options for a cost model and may not be mutually exclusive:

1. Government funding - fund from general government revenues 2. Updater funding - charge those who make changes to the dataset(s) 3. User funding - charge those who use the dataset(s)

Which of these should be used (note that option 2 is normally not an option but may be depending on the individual circumstances surrounding a dataset) will depend on the social, technological and political circumstances. Options 1 and 3 are always available but there may be cases where option 2 is feasible. These funding sources translate into charging policies, that is, the prices charged to external users and updaters. There are three basic charging policies to choose from:

1. Profit-Maximizing - Setting prices to maximize profit given the demand for the information where the assumption is that the PSIH will be more than fully funded from its revenues and so will not require any direct government funding. If the PSIH were a public sector organization the PSIH would return any profits it makes to the government. 2. Average-Cost or Cost-Recovery - Setting prices equal to the long term fixed costs relating to data production. Similar to profit maximizing it is assumed that the PSIH would not require direct government funding. 3. Margin-Cost (Zero-Cost) - Setting prices equal to the short-term marginal cost, i.e., the cost of supplying data to an extra user. With respect to digital data, this cost is essentially zero and marginal cost and zero cost pricing are identical. In this case, the PSIH’s revenues from maintaining and supplying information will fall below its costs and the PSIH will depend on direct government funding (or a subsidy) to continue its information operations.

In the profit maximizing and average-cost/cost-recovery model, strong control would be retained over the reuse and redistribution of the data while in the Margin-Cost of Zero-Cost no conditions on the reuse and redistribution of the data would be imposed.

The impact of data use based on these models may have a profound effect on the potential use of the data when it is “for-fee” or “for free”. If making government data open to the public is thought of like a utility, for example a water distribution system, usage or service fees are required to pay for the capital cost of infrastructure updates and operations costs. The same argument could be used for implementing user fees for access to public data. The quality of service depends on the ability to fund the delivery of public open data. It may be the case, however, that imposing user fees reduces the actual usage of data made available thereby reducing the business value of doing so. In the case of a margin-cost or zero-cost model, where the delivery of open data depends on the government subsidizing the effort, quality of service may be affected due to funding limitations. On the other hand, making public data available for no cost would likely result in more stakeholders using public open data. In either case, the value to the government entity is not realized directly from the process of making data available but indirectly through new value that is created as a result of making data open and accessible.

The two most common business models that will be used are: 1) profit-maximizing and 2) margin-cost (or zero cost). In the profit-maximizing business model, access to publicly available data would be available at a cost to the user. The cost structure (e.g., subscription, volume, type, etc.) is not addressed here but would be appropriate structures to evaluate if this were the chosen business model). This type of model is appropriate in a public-private partnership scenario since the user fees would be used to support the investment in the resources, technology and infrastructure required to support a public open data portal from a lifecycle perspective. In this case, the private entity would be a corporate entity that is in business to develop, deliver, manage and maintain an open data portal (the technical requirements for such a portal are significant and are discussed in a later section). The government would benefit from this type of relationship since the initial investment in the public data portal would be borne by the stockholders of the private entity. As part of the cost structure, the government may pay fees for: 1) usage of the portal, 2) feedback of usage metrics for both business and technical purposes and 3) maintenance, management and continual improvement of the consumer experience for accessing public data.

In the margin-cost or zero cost model, the government would have complete responsibility for funding the resources, technology and infrastructure required to make government open data available to public consumers. The entire financial support for the initiative would be borne by the government and there would be no user fees required for access to the data. An obvious modification of this method would be to charge from some data and not others. This is likely to be a controversial issue as the public consumers would be the judge of whether the data that they wish to access has more value (and they are willing to pay for it) than other data that is freely available.

Summary: Creating an open data system requires resources that may be a challenge for a government to be able to provide alone, and the risks associated with making public data available must be mitigated as much as possible. There are a variety of business models beyond government appropriation that should be considered.

References

[1] McKinsey Global Institute, “How Government can Promote Open Data and Help Unleash over $3 Trillion in Economic Value”, Government Designed for New Times, 2013.

[2] McKinsey Global Institute, “Open data: Unlocking innovation and performance with liquid information”,http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/business_technology/open_data_unlocking_innovation_and_performance_with_liquid_information, October 2013.

[3] Howard, A., “What is the ROI of open government?”, http://gov20.govfresh.com/what-is-the-roi-of-open-government/, March 2013.

[4] Sunlight Foundation, “Open Data Guidelines”, http://sunlightfoundation.com/opendataguidelines/.

[5]McKinsey Global Institute, “The social economy: Unlocking value and productivity through social technologies”, http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/high_tech_telecoms_internet/the_social_economy, July 2012.

[6] Burwell, S.M., VanRoekel, S., Park, T., and Mancini, D.J., “M-13-13 - Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies”, http://project-open-data.github.io/policy-memo/.

[7] Rowley, J., “e-Government stakeholders - Who are they and what do they want”, International Journal of Information Management 31 (2011) 53 - 62.

[8] Chircu, A.M., “E-government evaluation: Towards a multi-dimensional framework”, Electronic Government: An International Journal, 5(4), 345 - 363 (2008).

[9] Hedman, J., Lind, M., Olov, F. and Lars, M., “Business Models for Public Private Partnership: The 3P Framework”, Collaboration and Knowledge Economy, IOS Press, Amsterdam (2008).

[10] Pollock, R., “The economics of public sector information”, Cambridge University, Cambridge Working Papers in Economics, May 2009.